Managing Psoriatic Arthritis: Treatment Options and Care

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory condition that combines joint pain and stiffness with the skin changes of psoriasis. Treatment aims to reduce inflammation, control symptoms, slow joint damage, and support daily function. Options range from lifestyle measures and physical therapy to a variety of medications, injections, and, in selected cases, surgery. Treatment plans are individualized based on disease severity, affected joints, overall health, and treatment response.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

What is the medical approach to treatment?

Medical treatment for psoriatic arthritis typically follows a stepwise approach, starting with symptom relief and progressing to disease-modifying therapies when needed. Early use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can help prevent long-term joint damage. Clinicians assess disease activity, patterns of joint involvement, presence of enthesitis or dactylitis, skin severity, and coexisting conditions when choosing therapy.

Common strategies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain control, local corticosteroid injections for targeted inflammation, conventional DMARDs such as methotrexate or sulfasalazine for broader disease control, and escalation to biologic or targeted synthetic agents if symptoms persist or radiographic progression occurs.

How do biologic and targeted therapies work?

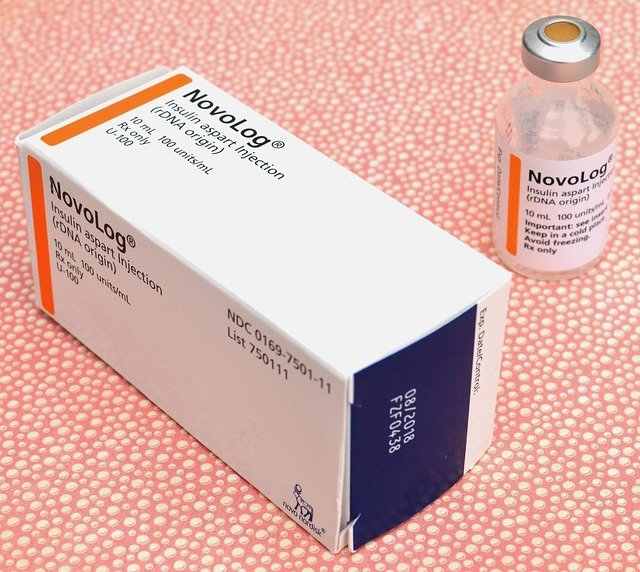

Biologic therapies target specific immune system molecules that drive inflammation. Examples used in clinical practice include tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors and interleukin (IL) inhibitors, which interrupt inflammatory signaling pathways contributing to both joint and skin disease. Targeted synthetic DMARDs, such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors and phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors, are oral medications that act on intracellular signaling pathways.

These agents can substantially reduce joint swelling, pain, and skin symptoms for many people. Because they affect the immune system, clinicians screen for latent infections (for example, tuberculosis) before starting treatment and monitor for adverse effects such as infections, laboratory abnormalities, or changes in cholesterol or liver enzymes.

What role do physical therapy and lifestyle measures play?

Physical therapy and regular, appropriate exercise are core components of long-term management. A physical therapist can design strength, flexibility, and aerobic programs that maintain joint range of motion, improve function, and reduce pain. Low-impact activities such as swimming, cycling, and walking are commonly recommended.

Lifestyle modifications — including maintaining a healthy weight, quitting smoking, and managing stress — can reduce systemic inflammation and improve overall outcomes. Occupational therapy may offer practical strategies and devices to reduce joint strain during daily activities. Sleep quality, balanced nutrition, and fall prevention strategies are also important for preserving mobility.

When are injections or surgery considered?

Local corticosteroid injections can be useful for persistent inflammation in single joints or entheses and are frequently used to provide rapid symptom relief. They are typically considered alongside systemic treatments and physical therapy.

Surgery is an option when structural joint damage leads to severe pain, deformity, or loss of function that does not respond to conservative measures. Procedures range from synovectomy and joint debridement to joint replacement in advanced cases. Surgical decisions are individualized and follow thorough assessment by rheumatologists and orthopedic surgeons.

How is treatment monitored over time?

Regular follow-up is essential. Monitoring typically includes clinical assessment of joint counts and function, patient-reported symptoms, skin disease severity, and periodic laboratory tests (for example, blood counts, liver and kidney function, and inflammatory markers) depending on the medications used. Imaging such as X-rays or MRI can document structural changes when indicated.

Treatment goals and targets are agreed upon between clinician and patient; if improvement is insufficient, adjustments in medication type or dose, combination therapy, or referral to specialty services may be necessary. Coordination among dermatology, rheumatology, physical therapy, and primary care improves comprehensive management.

Conclusion

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic condition that requires individualized, multidisciplinary care. A combination of medication, physical therapy, lifestyle changes, and, when needed, injections or surgery can help control inflammation, reduce symptoms, and preserve function. Ongoing monitoring and communication with healthcare providers support optimal long-term outcomes.