Myelofibrosis Treatment: Medical Options and Symptom Management

Myelofibrosis is a chronic bone marrow disease that disrupts blood cell production and causes symptoms ranging from fatigue to an enlarged spleen. Treatment focuses on controlling symptoms, improving blood counts, and slowing disease complications. Management choices depend on disease severity, patient age, symptom burden, and laboratory findings; options range from supportive care to targeted drugs and, for some patients, stem cell transplant.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

What is myelofibrosis and its disease course?

Myelofibrosis is a type of chronic myeloproliferative disease in which scar tissue replaces normal bone marrow, impairing its ability to make healthy blood cells. The disease course varies widely: some people have stable symptoms for years, while others develop progressive cytopenias, splenomegaly, or transformation to acute leukemia. Regular monitoring with blood counts, physical exams, and periodic bone marrow evaluation helps clinicians assess progression and adjust medical management accordingly.

How does myelofibrosis affect the bone marrow?

Fibrosis in the bone marrow disrupts normal architecture and hematopoiesis, so the body may shift blood production to other organs such as the spleen and liver. This extramedullary hematopoiesis often causes enlargement of those organs and contributes to symptoms like abdominal fullness or pain. Bone marrow biopsy is the diagnostic tool used to confirm the extent of fibrosis and cellularity; findings guide decisions about medical therapy and eligibility for more intensive interventions like transplant.

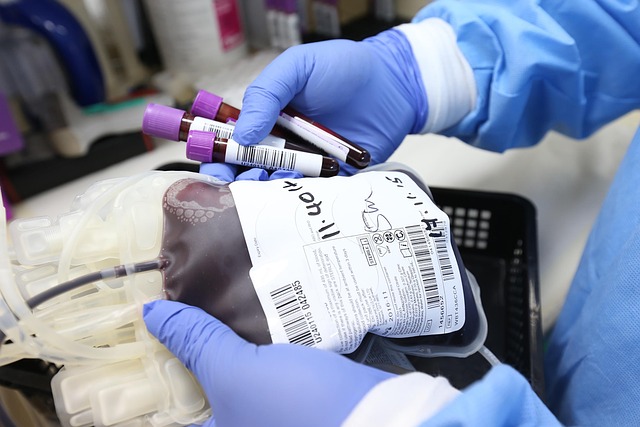

Why myelofibrosis leads to anemia

Anemia in myelofibrosis arises from reduced red blood cell production in fibrotic marrow, shortened red cell lifespan, and sometimes from splenic sequestration. Anemia contributes substantially to fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance. Treatment may include red blood cell transfusions, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for selected patients, androgen therapy in some settings, or targeted drugs that can improve marrow function. Clinicians balance benefits against risks such as iron overload from repeated transfusions and monitor iron levels when appropriate.

Medical treatment options and targeted drugs

Medical treatment aims to reduce symptoms, control organ enlargement, and improve blood counts. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are commonly used to reduce splenomegaly and constitutional symptoms in many patients. Other medical options include cytoreductive agents such as hydroxyurea for high blood counts, interferon for select patients (especially younger ones), and supportive medications for infections or bleeding. For anemia-predominant disease, clinicians may trial erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or thrombopoietin receptor agonists in carefully selected cases. Treatment must be individualized and reassessed periodically.

Managing fatigue and supportive care

Fatigue is one of the most frequent and debilitating symptoms. Supportive care strategies include treating contributory factors such as anemia, addressing sleep and nutrition, and using physical therapy or exercise programs adapted to capacity. Symptom-directed medications and psychosocial support can improve quality of life. Palliative care services are appropriate for symptom relief at any stage and can be integrated alongside disease-directed therapies to manage pain, fatigue, and emotional burden.

When to consider transplant or clinical trials

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant is the only potentially curative option but carries substantial risks and is generally reserved for patients with higher-risk disease or those with disease features suggesting progression. Eligibility is influenced by age, comorbidities, donor availability, and patient preferences. Clinical trials remain important for access to novel agents and combinations targeting molecular drivers of the disease. Discussion with a hematologist at a specialized center can clarify candidacy for transplant or trial enrollment and provide up-to-date medical perspectives.

Conclusion

Myelofibrosis treatment spans a spectrum from supportive measures to targeted therapies and transplantation, guided by symptom burden, blood counts, and individual goals of care. Managing anemia, monitoring bone marrow status, reducing fatigue, and addressing splenomegaly are central components of medical management. Decisions about aggressive therapies such as transplant or experimental agents require multidisciplinary evaluation and weighing of risks and benefits. Ongoing follow-up and symptom-focused care help maintain quality of life throughout the disease course.