Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Treatment Options and Care

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a dilation of the main artery in the abdomen that can progress without symptoms and, in some cases, lead to serious complications. Early detection, appropriate monitoring, and timely treatment decisions are central to minimizing risk. Management often involves collaboration between a primary doctor, vascular specialists, imaging teams at a hospital, and patients who must weigh medical and surgical options. This article outlines common pathways of care, what patients can expect, and typical tests and treatments used in contemporary practice.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

Doctor: When to consult a specialist

If you or your primary care doctor suspects an abdominal aortic aneurysm, timely referral to a vascular specialist or surgeon is important. Signs that warrant faster evaluation include a newly discovered pulsatile abdominal mass, unexplained abdominal or back pain, or a rapid increase in known aneurysm size. Primary care physicians often identify risk factors—such as age, smoking history, and cardiovascular disease—and arrange initial screening imaging. A specialist will review the imaging, assess surgical risk, and discuss surveillance versus intervention. Shared decision-making between the doctor and patient helps determine the most appropriate approach for individual circumstances.

Patient: Symptoms and monitoring

Many patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm have no noticeable symptoms and learn of the condition during routine exams or imaging for other reasons. When symptoms occur they can include persistent abdominal or back pain, a sense of fullness, or, rarely, a noticeable pulsating mass. Patients with a diagnosed aneurysm typically enter a surveillance program with periodic imaging to monitor size and growth rate. The frequency of follow-up imaging is tailored to each patient’s situation, balancing the aneurysm’s behavior and the patient’s overall health, and the patient’s role in reporting new symptoms is essential.

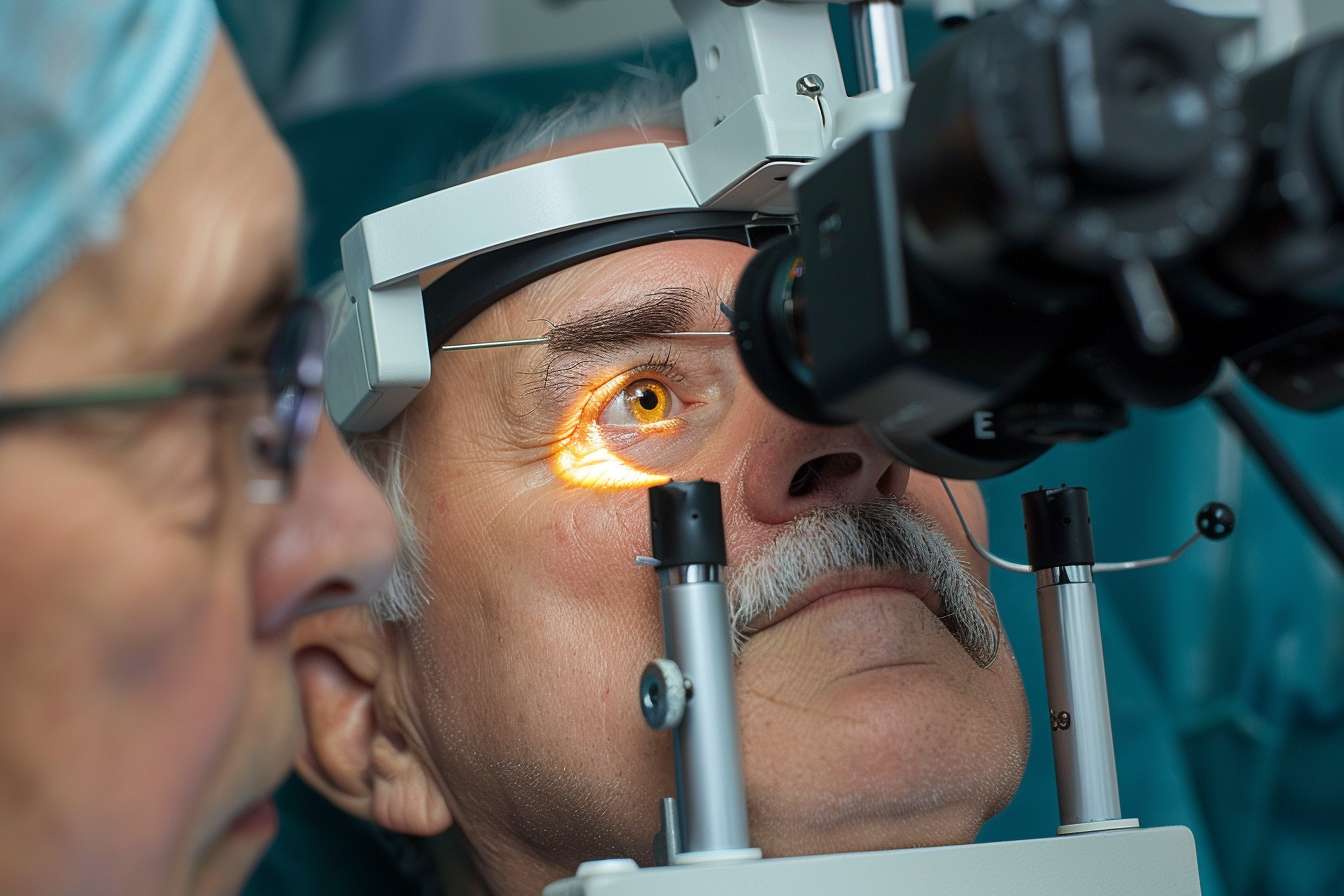

Hospital: Diagnostic imaging and assessment

Hospitals and imaging centers use abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) angiography to diagnose and characterize an aneurysm. Ultrasound is commonly used for initial detection and routine surveillance because it is noninvasive and widely available; CT angiography provides detailed views of aneurysm anatomy and is frequently used when planning intervention. Pre-treatment hospital assessment often includes evaluation of cardiovascular fitness, renal function, and other comorbidities to inform risk stratification. Multidisciplinary care in the hospital—linking radiology, anesthesia, cardiology, and vascular teams—improves planning for either medical management or procedural care and helps coordinate local services in your area.

Medical: Non-surgical management

Medical management focuses on reducing cardiovascular risk and slowing aneurysm progression where possible. Key elements include blood pressure control, smoking cessation, lipid management, and treating other comorbid conditions such as diabetes or coronary artery disease. Medications do not reverse an aneurysm, but optimizing cardiovascular health can lower the overall risk of complications. Regular imaging surveillance remains a cornerstone of medical management; changes in size or new symptoms prompt re-evaluation. Patient education about warning signs and adherence to medical therapy are important components of non-surgical care.

Surgery: Endovascular and open repair

When intervention is recommended, two primary surgical approaches are used: endovascular repair and open surgical repair. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is a minimally invasive technique in which a stent graft is placed through arteries to exclude the aneurysm from blood flow; it often entails shorter hospital stays and faster initial recovery. Open repair involves a larger abdominal incision to replace the diseased aortic segment with a graft and may be chosen based on aneurysm anatomy or patient factors. Each approach carries specific risks—bleeding, infection, kidney or cardiac complications, and the possibility of future interventions—and the choice of surgery is individualized based on anatomy, surgical risk, and patient preferences. Long-term surveillance, especially after EVAR, is typically required to check graft position and address any endoleaks or other changes.

Conclusion

Abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment involves a spectrum of care from surveillance and medical risk-factor management to planned intervention with endovascular or open surgery. Decisions rely on input from doctors and specialists, diagnostic imaging performed in the hospital setting, and an informed patient understanding of medical and surgical options. Regular follow-up and attention to cardiovascular health help guide timing of treatment and reduce risk over time.