Addressing comorbidities and drug interactions in tuberculosis management

Managing tuberculosis alongside other medical conditions requires coordinated diagnostic, pharmacological, and monitoring strategies that reduce harm and preserve treatment effectiveness. This article outlines practical approaches to identify comorbidities, assess drug–drug interactions, adjust regimens, and support adherence while minimizing risks to pulmonary and systemic health.

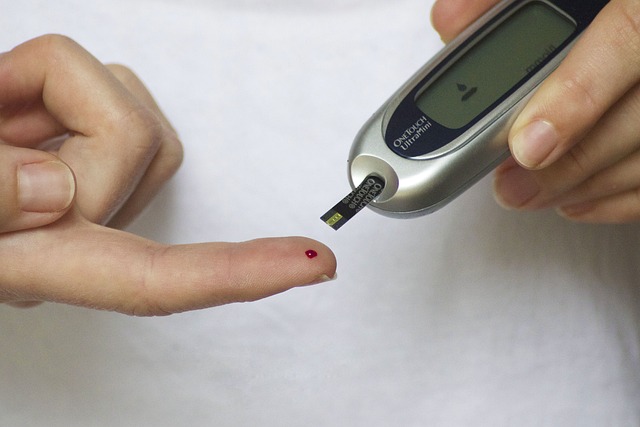

Managing tuberculosis in patients with additional medical conditions presents clinical and programmatic challenges that affect diagnosis, treatment selection, and outcomes. Recognizing common comorbidities such as HIV, diabetes, chronic lung disease, and liver or kidney impairment is essential from the moment TB is suspected. Comorbidities can alter clinical presentation, influence the choice and dosing of antibiotics and regimens, and increase the risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Early, systematic assessment supports safer, effective care across the treatment course.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

How does diagnosis affect TB care?

Accurate diagnosis is the foundation for managing tuberculosis with comorbidities. In addition to microbiological confirmation (smear, culture, or molecular tests), clinicians should perform baseline assessments that include chest imaging and tests relevant to suspected comorbidities. For example, HIV testing and CD4 count, glycemic status for diabetes, liver and renal function tests, and screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other pulmonary pathology refine risk assessment and guide regimen selection. Diagnostic delays or missed comorbid conditions can lead to suboptimal treatment choices, increased toxicity, or poorer outcomes.

What screening should be done?

Routine screening at TB diagnosis should include targeted evaluations for conditions that commonly coexist with TB. Universal HIV screening, blood glucose or HbA1c for diabetes risk, and assessment for substance use are frequently recommended. Baseline liver enzymes and creatinine are important before starting hepatotoxic or renally-excreted antibiotics. Vaccination status (where relevant) and infection control risk in households or clinics should be evaluated. Screening permits timely interventions that reduce complications and inform infection control measures within healthcare settings and communities.

How are antibiotics and regimens chosen?

Regimen selection must balance efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis with safety in the context of comorbidities and concomitant medications. Standard pulmonary regimens may require dose adjustments or substitutions when patients have hepatic impairment, severe renal dysfunction, or co-administration of interacting drugs (for example, some antiretrovirals). Shorter or modified regimens for drug-susceptible TB still rely on core antibiotics whose pharmacokinetics can change with age, weight, nutrition, and organ dysfunction. Multidisciplinary input from infectious disease, pharmacy, and specialty teams improves individualized regimen planning.

How does drug resistance change management?

Drug resistance complicates interactions and comorbidity management because second-line agents often have different toxicity profiles and interaction risks. Drugs used in multidrug-resistant TB regimens may prolong QT interval, be ototoxic, nephrotoxic, or interact with antiretrovirals and other chronic medications. When resistance is suspected or confirmed, expand laboratory testing and consult pharmacology expertise to select compatible combinations, adjust dosing, and plan enhanced monitoring. Preventing acquired resistance depends in part on addressing adherence barriers that are often more pronounced in patients with multiple health needs.

How to support adherence and compliance?

Adherence is critical to prevent treatment failure and resistance, and comorbidities frequently undermine compliance. Practical measures include synchronizing medication schedules where possible, simplifying pill burdens, using directly observed therapy or digital adherence tools when appropriate, and coordinating management of comorbid conditions to reduce clinic visits and prescription conflicts. Patient education about potential interactions and side effects, social support for transport or nutrition, and regular review of concomitant medications can reduce interruptions. Collaboration with community health workers, pharmacists, and patient support services enhances long-term compliance.

What are key pharmacology and monitoring considerations?

Understanding pharmacology is central to preventing harmful drug–drug interactions. Many anti-TB antibiotics are metabolized hepatically or rely on renal clearance; some induce or inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes affecting other drugs. Regular monitoring should include clinical assessment, baseline and periodic liver and renal tests, therapeutic drug monitoring when available (for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows), ECG monitoring for QT-prolonging agents, and audiometry for ototoxic drugs. Adjustments should be made proactively for age, pregnancy, malnutrition, or organ dysfunction. Infection control precautions remain important in pulmonary disease to limit nosocomial and household transmission.

Conclusion Addressing comorbidities and drug interactions in tuberculosis management requires integrated diagnostic pathways, careful regimen selection, proactive pharmacologic review, and tailored adherence support. Multidisciplinary collaboration, routine screening for common coexisting conditions, and systematic monitoring reduce risks and improve outcomes. Clinicians should use current local and international guidelines and consult pharmacology or infectious disease specialists when complex interactions or organ dysfunction arise.