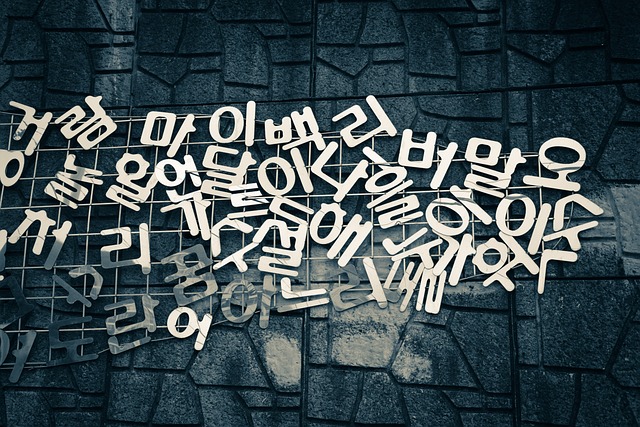

Font Design and Typography Fundamentals

Good font design turns letters into a clear, usable system that supports communication and brand personality. It combines technical skills — like vector drawing and kerning — with visual judgment about proportion, contrast, and spacing. For anyone working with text, from UI designers to editors, understanding font design improves legibility, tone, and the overall reading experience.

How are fonts structured?

A font is a collection of glyphs: the visual representations of characters, punctuation, and symbols. Each glyph is built from outlines (vectors) that define strokes, counters (the enclosed or partially enclosed spaces), and terminals. Beyond the shapes, metadata—such as metrics, kerning pairs, and OpenType features—governs how glyphs space and behave across contexts. Good font structure anticipates how text scales, adapts to weight variations, and supports multilingual characters.

Fonts are often organized into families with multiple weights and styles (regular, italic, bold). Designers plan consistent proportions and stroke contrasts so the family works as a cohesive toolkit across sizes and media.

Typography and readability

Typography is the craft of arranging text to make written language legible, readable, and appealing. Readability depends on typeface choice, line length, leading (line spacing), and weight. A well-considered typographic system uses hierarchy—size, weight, and spacing—to guide readers through content. For body text, moderate stroke contrast and open counters generally aid sustained reading; display type can use more distinctive features to create character at larger sizes.

Accessible typography also accounts for screen rendering: hinting and hint-aware design help characters render crisply at small sizes, while variable fonts can provide adaptive weight and width to improve readability across devices.

What impacts text legibility?

Legibility refers to how easily individual characters are distinguished. Factors that influence legibility include x-height (height of lowercase letters), stroke contrast, serif presence, terminal shapes, and spacing. High x-heights and open counters typically improve legibility at small sizes, while excessive contrast or ornate terminals can reduce clarity.

Context matters: printed text behaves differently from on-screen text, and lighting, screen resolution, and viewing distance all change perception. Testing fonts in real-world contexts (sample paragraphs, narrow columns, and different resolutions) is essential to ensure legibility goals are met.

Principles of type design

Type design balances aesthetics and function. Key principles include consistency of stroke width and curve construction, harmonious proportions between uppercase and lowercase, and a robust set of diacritics for international use. Designers also plan metrics—sidebearings and vertical metrics—that determine how text flows in layouts and software.

The iterative process typically starts with sketching core letters (like “n,” “o,” “H,” “n,” and “e”) to establish rhythm, then expands to complete the alphabet and punctuation. Modern workflows use vector tools and build OpenType features (ligatures, contextual alternates) to enrich typographic behavior without compromising core structure.

When to use serif fonts?

Serif fonts include small projecting strokes at the ends of letterforms, historically linked to print and body text. Serifs can aid horizontal reading by creating a subtle guide for the eye across a line, which is why many long-form printed works use serif types. That said, on low-resolution screens or very small sizes, serifs can blur and reduce clarity; sans-serif faces often perform better in such conditions.

Choosing a serif is a matter of tone and function: transitional and old-style serifs convey tradition and formality, while slab serifs feel more robust and contemporary. Consider the medium, audience, and brand voice when deciding whether a serif supports the intended reading experience.

Testing and refining font designs

Beyond drawing shapes, successful font projects include rigorous testing and refinement cycles. Proofing in paragraphs, columns, and UI mocks reveals spacing and weight issues that single glyph review can miss. Tools for automated spacing tests and user feedback sessions help catch readability or pairing problems. Attention to kerning, hinting, and feature implementation ensures the font behaves predictably across platforms.

Designers also consider licensing, character set needs, and technical distribution formats (OTF, TTF, variable fonts). Collaboration with developers and content strategists helps align the type system with real content demands and performance constraints.

Conclusion

Font design is both an art and an engineering discipline: it involves drawing consistent, expressive letterforms and encoding behavior that supports reading across media. By focusing on structure, legibility, and practical testing, designers create typefaces that serve communication needs while contributing distinct visual character to text.